The Contest Winners Are

Big time CONGRATULATIONS! to the winners of our Micro Fiction Contest. Their names, the names of their pieces, and the dates they will appear are below.

Big time CONGRATULATIONS! to the winners of our Micro Fiction Contest. Their names, the names of their pieces, and the dates they will appear are below.

There’s a lot of variety in these pieces. You can read why each one appealed below the story.

1-02-26 Arielle King’s “Split”

1-06-26 Carol Blatter’s “Fall in Three Acts”

1-13-26 Gargi Mehra’s “Fuzzy Logic”

1-20-26 Claire Massey’s “Lost and Found: Titanic Victim #325”

1-27-26 Jeffrey-Michael Kane “Taxonomy and Inventory”

2-03-26 Laurie Lewis’s “The Fire”

2-10-26 Van Wallach’s “In the Wee, Small Hours”

Three more micros will be posted–one per week. Please come back each Tuesday to read them.

Do you have a Flash Memoir? Please look at our Latest Contest. We want to read your story. Thanks!

Taxonomy

By J.M.C. Kane

My son asks why we name hurricanes after people. I tell him it started with wives and girlfriends —unpredictable, the military meteorologists said, temperamental—until someone complained and they added men to the list. He’s quiet, then: “Why do they get names only when they promise to hurt something?”

My son asks why we name hurricanes after people. I tell him it started with wives and girlfriends —unpredictable, the military meteorologists said, temperamental—until someone complained and they added men to the list. He’s quiet, then: “Why do they get names only when they promise to hurt something?”

I don’t know the answer. I check. There isn’t one.

That night he asks if I’d still love him if he were a hurricane. I say yes, even the ones they run out of names for. The ones they have to call by Greek letters because the alphabet gave up.

Inventory

By J.M.C. Kane

The pharmacist asks if I’m taking anything else. I say no, which is true if we’re only counting pills.

I don’t mention the part where I’ve been wearing the same shirt for six days. Or how I’ve started buying groceries in units of one—one apple, one can of soup—because planning for Thursday feels like a broken promise.

She scans the barcode. The register beeps.

“Any questions about side effects?”

I want to ask if emotional weather counts. If there’s a diagnosis for feeling like furniture.

Instead: “No, I’m good.”

The bag crinkles. I tell it to hush.

@@@

J.M.C. Kane is a writer from England, though now claimed by New Orleans, who has spent most of his adult life trying to fit long stories into short boxes. He has worked as a paperboy, a contracting executive, and an amateur cataloguer of human regret—none of which he was formally trained for. His fiction has appeared in almost three-dozen journals that appreciate compression—and his willingness to obey word counts.

Editor’s note: We love the brevity and the insights. It takes a special skill to write this tightly. Good job!

@@@

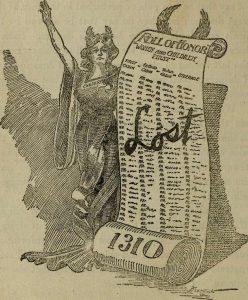

Lost and Found: Titanic Victim #325

By Claire Massey

My final thoughts were of the firmament above me, icy stars blanketing the sky from horizon to horizon, unfathomable, incapable of warmth. How many nights would I drift beneath them, these silent witnesses to man’s folly; an impervious galaxy wheeling on, epoch after epoch.

My final thoughts were of the firmament above me, icy stars blanketing the sky from horizon to horizon, unfathomable, incapable of warmth. How many nights would I drift beneath them, these silent witnesses to man’s folly; an impervious galaxy wheeling on, epoch after epoch.

They found my body but lost my name. The mates of the Mackay-Bennett, the “death ship” summoned by the White Star Line to snatch floaters from the drink made scrupulous notes to aid identification when the dead wore fine overcoats with London labels and sewn-in compartments, heavy with coin, and gold, engraved watches.

But my paragraph was sparse, unyielding.

It read:

Unidentified male, estimated age 23. Brown hair, light moustache. Tattooed right arm, anchor and rose. Steward’s white jacket and dungaree pants. Plain brass ring on little finger. Six pawn tickets in possession from shop with Southampton address.

Thus was my body, hooked like a sailfish yanked from the sea, returned to the deep with the briefest of ceremony and a reverend’s pronouncement that my name was known only to God.

My greater losses, of course, were the second chances a lived life affords. Options to forgive the drunkard father from wandering afar, to break with the wrong girl and marry the right one, to realize ambitions that lift one above the class and rank assigned at birth.

But something much larger than the potentialities of a single life was found, something world-altering, momentous. There occurred a sea change in thought about arrogant pride in technology, the limitations of human mastery, the wrongness of devaluing seven hundred souls in steerage. The “foreign” women frozen with babes in arms, the valets and nannies, crewmen and stewards, the stokers of coal from Titanic’s bowels, could not have imagined the impact of their legacy. Empires were warned of nature’s supremacy, learning anew that the elements are untamable. Safety must triumph over speed, every child birthed has promise, every existence purpose, all deserving of a lifeboat’s seat.

Before I closed my eyes against the Milky Way, spilling stars like diamonds lost to the sea, I recalled lines from a poem by Lord Byron. We were made to memorize it as students in fifth form.

“Roll on, thou deep and dark blue ocean–roll

Ten thousand fleets sweep over thee in vain;

Man marks the earth with ruin—his control

Stops with the shore.”

Author’s note: After a public outcry against so many “nameless”’ burials at sea, the White Star Line paid for 150 victims of the Titanic disaster to be interred in Halifax, Nova Scotia cemeteries. There were over 1500 victims; the largest percentage from crew and steerage/third class.

@@@

Claire Massey enjoys writing hybrid flash forms that interweave elements of fiction, memoir, and essay. Her work, which often explores themes of resistance to oppression, appears in over sixty venues for the literary arts and in her collections, Driver Side Window and Awake in the Sacred Night.

Editor’s note: This is original and personalizes a tragic loss. It took me into history in a new and refreshing way. Good insights into the unknown life of someone who died too soon.

@@@

Fuzzy Logic

By Gargi Mehra

The wild frizz confirms it’s my mother.

The wild frizz confirms it’s my mother.

While the attendant helps her into a chair, I remember how she used to moan – oh look, I have only two hairs.

And look now, after all these years it’s come true quite literally.

She sits bug-eyed, her lashes spare, yet I long for recognition.

But then I remember – she died long ago.

Now it’s only me glaring at the mirror.

@@@

Gargi Mehra is a writer, a computer engineer, and a mother. She plays the piano and thrives on word games including crosswords, Scrabble and Wordle. Her creative writing has appeared in several literary magazines online and in print. She lives with her husband and two children in Pune, India.

Editor’s note: We love the validity and universality of this exact moment and we’re impressed by how quickly and effectively the narrator makes her point without hitting readers over the head. The concise build to the ending is powerful.

@@@

Fall in Three Acts

By Carol J. Wechsler Blatter

I. When fall arrived, I remember feeling more energized and excited. Casual long-sleeve polo shirts, long pants, and sweaters replaced my lightweight summer garb. And proudly I wore new clothes for school, skirts and blouses. Mom made sure I was well dressed.

I. When fall arrived, I remember feeling more energized and excited. Casual long-sleeve polo shirts, long pants, and sweaters replaced my lightweight summer garb. And proudly I wore new clothes for school, skirts and blouses. Mom made sure I was well dressed.

Leaves fell, sending a panoply of yellow, red, rust, and brown leaves to the ground. I remember the crunching sound of dead leaves being raked into piles, bagged, and readied for garbage pickup. And children wore light coats and jackets trick-or-treating on Halloween as the temperatures cooled. Fall left too quickly. Winter’s chill winds were waiting in the wings.

II.

Fall in Tucson is not a clearly defined season, but as a cooler continuation of summer with shorter days and longer nights, a few dark days, dull and bleak, accompanied by rain, always in short supply, with puffy white pockets of fluff on the mountain tops and in the sky. Gradual changes occur, like hummingbirds and hawks migrating south, pumpkins with carved faces seen on porches, some with candles inside lit up at night, restaurant menus are often decorated with fall colors, yellows, oranges, browns, and crimson, and include yummy, enticing desserts like pumpkin bread, pumpkin muffins, and pumpkin cheesecake.

(100 words)

III.

I’m fortunate my birthday occurs during fall in October, after summer’s heat has lessened and Tucson’s weather is perfect with warm days and cool, crisp, comfortable nights. Until then, I never worried about my age or my health. I didn’t need to. Then everything changed. I experienced excruciating pain from three fractured spinal vertebrae due to osteoporosis, which were later repaired. I’m a few inches shorter. My breasts, diaphragm, and belly are squeezed together. This is uncomfortable but not life-threatening. Physical therapy and daily walks are strengthening my spine and stamina. I am blessed. I am healing. Happily, I’m eighty-three.@@@

Carol J. Wechsler Blatter is a recently retired psychotherapist. She has contributed writings to Chaleur Press, Real Women Write, The Power of Friendship, and In The Garden anthologies, Writing it Real anthologies, Jewish Writing Project, Jewish Literary Journal, The Gift of Long Life, Personal Stories on the Aging Experience in the 2024 Birren Center Collection.

Editor’s Note: This collection of 3 Drabbles is a personal and universal timeline that many readers should identify with. The range of ideas and specificity both work well here.

@@@

Split

By Arielle King

Nearing twenty-four, my mother split in two. The Her that stayed with us missed the Her that was gone. We felt she wanted to be somewhere else. Having a mother who wasn’t fully herself was difficult.

Nearing twenty-four, my mother split in two. The Her that stayed with us missed the Her that was gone. We felt she wanted to be somewhere else. Having a mother who wasn’t fully herself was difficult.

Now I’m the age she was when she split. I keep photos of her in her twenties. I pull them out at night and look at her before bed. I look to make sure I am still myself. I look and then close my eyes and repeat I am whole; I am not her. I am whole. I am not her.

@@@

Arielle King lives in Gainesville, FL, with her husband and their two dogs. She earned her BA from the University of Florida in 2017. She is currently writing microfiction and expecting her first child.

Editor’s Note: The narrator makes her point with conviction. The compression is outstanding. Great job!